By the time the doors opened Tuesday morning, January 20th, the Wylie High School Performing Arts Center already told a story.

Extension cords snaked along the floor. Batteries sat charging in rows, ready for rotation. Black-and-white field markers were aligned with care—close enough to pass inspection by a robot’s camera, but precise enough to satisfy a group of teenagers who know that an inch can be the difference between success and failure.

And that story started a day earlier.

While most of the campus enjoyed a Monday holiday, Mr. John Vann and members of the Wylie High School robotics team were inside the PAC—working overtime, hauling equipment, wiring fields, testing systems, and resetting layouts again and again until everything was right. It wasn’t required. It wasn’t for extra credit. It was because students from across Wylie ISD were coming together for something bigger than a competition.

“This wouldn’t be happening without Mr. Vann,” one student said plainly. And it wasn’t said for effect—it was said as fact.

By Tuesday, the space no longer felt like a theater. It felt like a community workshop, a broadcast studio, and a proving ground all rolled into one.

Robots zipped across the floor. Students cheered. Announcers filled the air with play-by-play. And between the buzz of motors and the swapping of batteries, something quieter—but far more powerful—was happening.

This wasn’t just robotics.

It was belonging, built piece by piece.

A Program That’s Growing—On Purpose

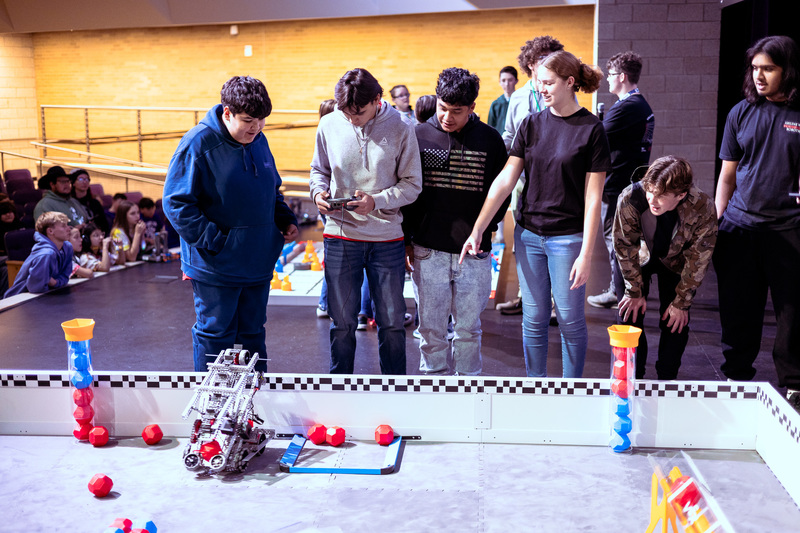

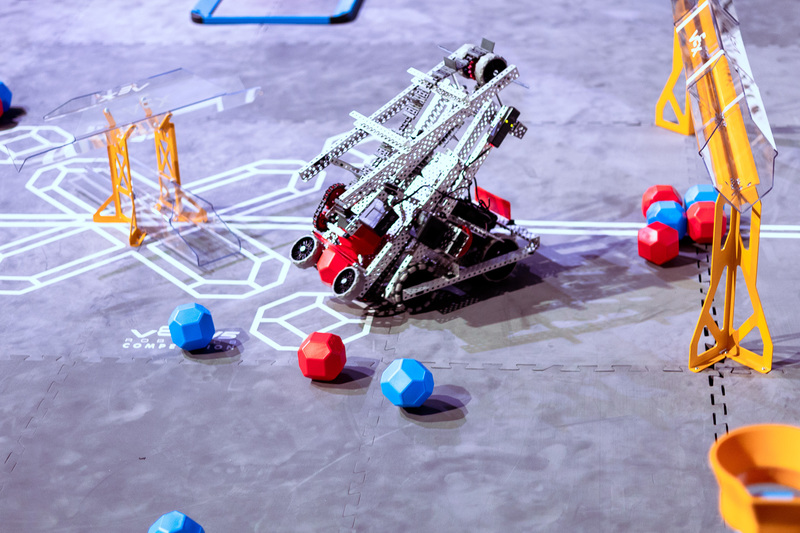

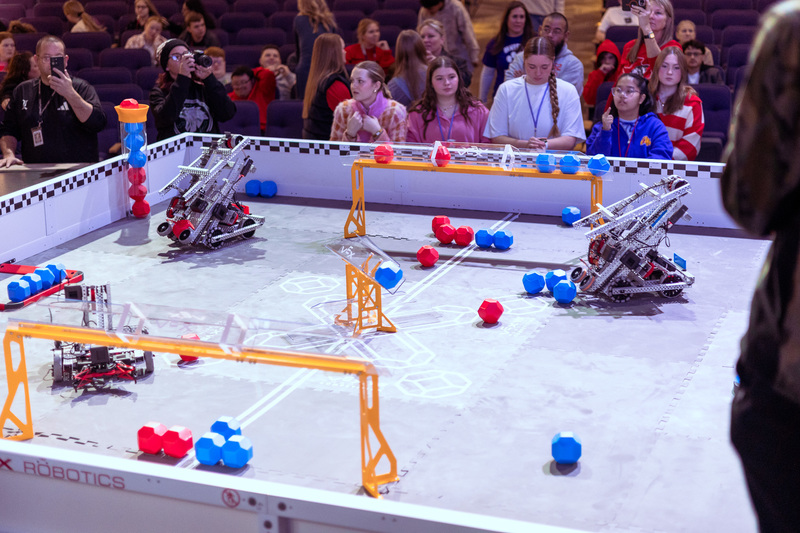

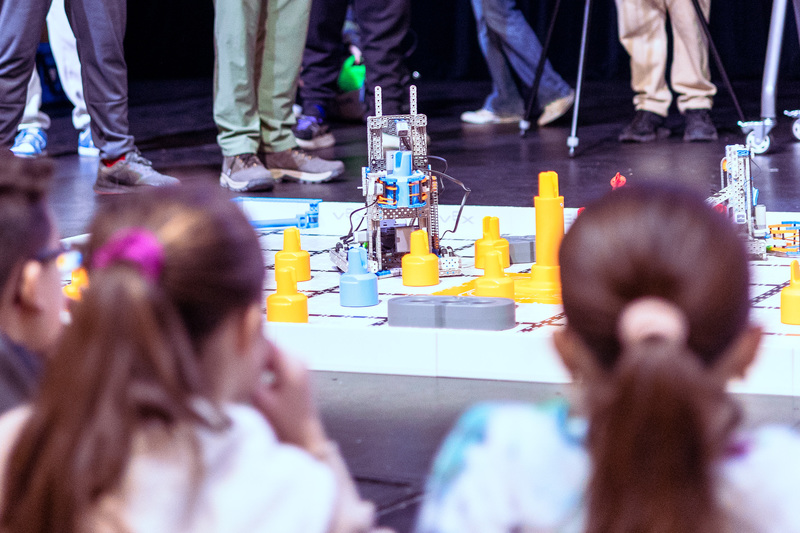

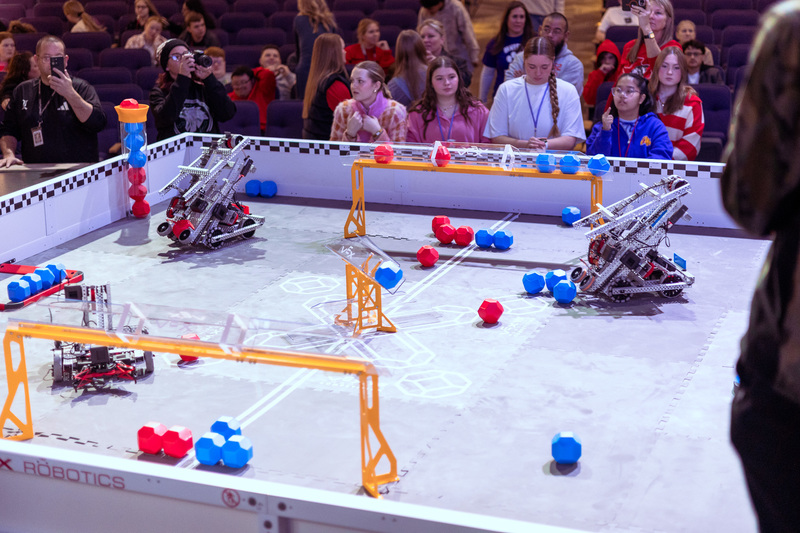

The event, hosted by the Wylie Robotics team, brought together students from Wylie East Junior High and Wylie West Junior High for a Special Olympics Unified Robotics competition. Supported by the REC Foundation and built around VEX Robotics, the tournament featured both VEX IQ fields for junior high teams and a full VEX V5 field—the same level used by high school and university competitors.

To an outside observer, it might have looked like a standard robotics tournament: timed matches, scoring goals, autonomous periods, alliances forming and reforming.

But that view misses the heart of it.

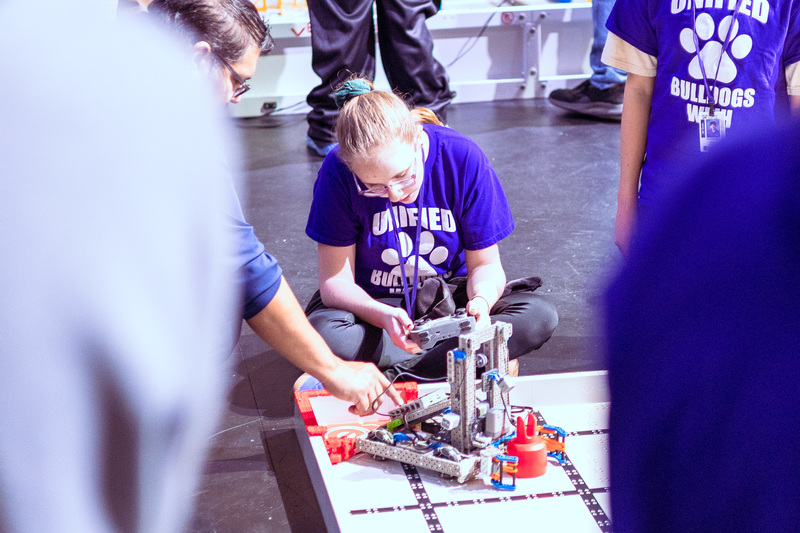

This was a Unified event—meaning teams were intentionally designed with equal numbers of Special Olympics athletes and student partners. Controllers were shared. Roles rotated. Everyone drove. Everyone built. Everyone competed.

And everyone belonged.

“This isn’t special education and general education playing together,” said Tammy Hortenstine, Executive Director of Unified Programs for Special Olympics. “It’s individuals with intellectual disabilities competing alongside partners—with equal roles and meaningful involvement.”

That distinction matters. Because in Unified robotics, no one is there to observe. No one is there just to assist. Everyone is there to participate.

Robots as the Vehicle, Not the Destination

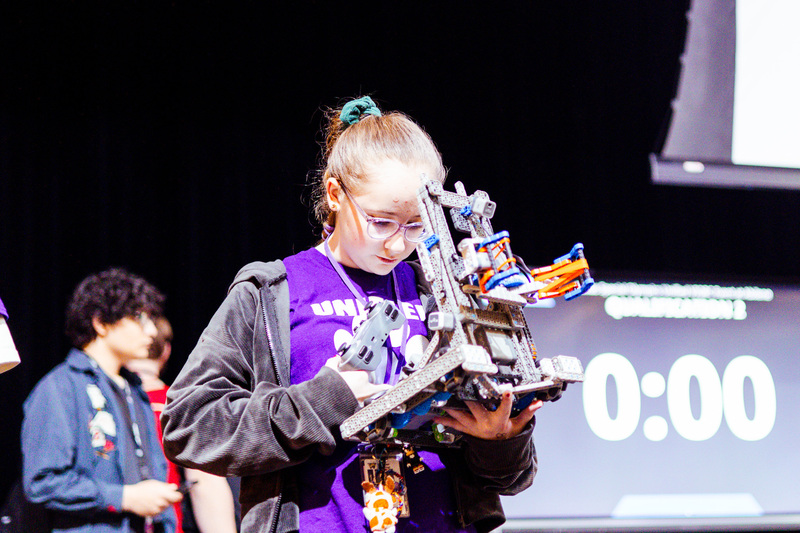

(James Betteridge, far right)

Eighth-grader James Betteridge from Wylie West Junior High stood near his team’s robot, describing a process that sounded a lot like any engineering lab.

The robot had broken more than once. Batteries drained faster than expected. Controls had to be switched mid-match. Adjustments were constant.

But what stuck with him most wasn’t the mechanics.

“Just being able to go with friends and play with robots,” James said. “That’s probably what I’ll remember.”

James’ team included Functional Academics students he hadn’t known well before robotics. Working together—practicing, troubleshooting, competing—changed that.

“We’ve all gotten to know each other way better by doing this,” he said.

That theme came up again and again throughout the day.

Robotics created the reason to gather. Unified design created the reason to connect.

And those connections didn’t end when the match timer stopped.

Hortenstine has seen this pattern across the state. “We’re seeing partners and athletes start getting invited to birthday parties, to dances, out for pizza,” she said. “They’re forming real friendships—off the field.”

That’s the kind of outcome you can’t program into a robot—but you can design into a system.

Student Leadership, Front and Center

(Tyler Hawks (center) records scores as Luke Preston leads live commentary for the robotics competition.)

(Tyler Hawks (center) records scores as Luke Preston leads live commentary for the robotics competition.)

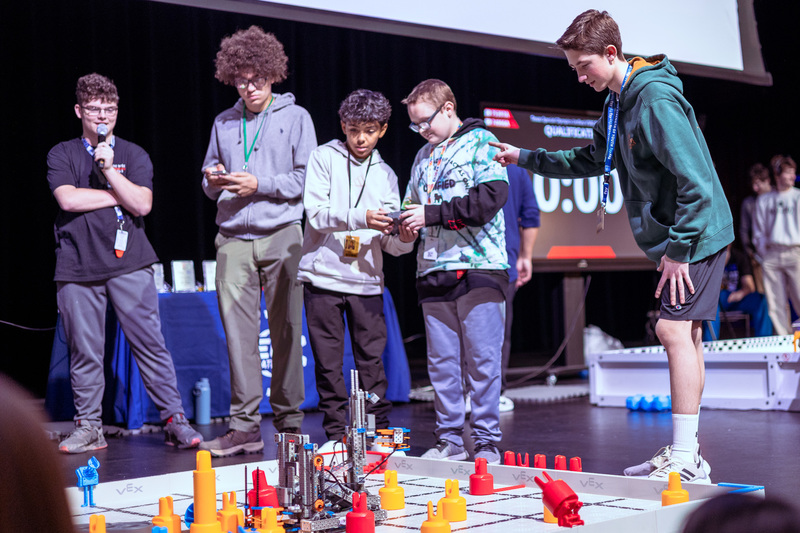

While multiple teams competed on the floor, Wylie High Robotics were everywhere else—running the event with the calm focus of people who knew they owned it.

Juniors Luke Preston, Wyatt Fordyce, and Tyler Hawks—members of the Wylie High School robotics team—were part of that effort. Under the leadership of Mr. Vann, they helped set up fields, reset matches, referee games, keep score, and troubleshoot problems as they arose.

Their team, officially registered as 31098A, goes by the name Village Idiots: Done and Dusted. The number functions like a license plate in the VEX world—earned through registration, proudly displayed, and instantly recognizable to other teams.

“This is our first real competition,” Preston said. “We’re learning as we go.”

Learning, in this case, didn’t mean sitting back and watching.

It meant coming in on a holiday to help set up. It meant taking off shoes to step onto the field for resets—over and over again. It meant refereeing matches with rules they were still mastering themselves. And it meant doing all of it knowing younger students were watching.

“We want to see how many different designs are out there,” Preston said. “And just see how a real competition plays out.”

This was as much a test run for Wylie’s growing robotics program as it was a competition—and the students knew it.

Engineering With Real-World Impact

Inside Wylie High School’s engineering and robotics classrooms, learning looks different than it did even a few years ago.

Students design using CAD software—the same tools used by professional engineers. They work with 3D printers, experiment with materials, and troubleshoot designs that don’t work the first time. In some cases, students can even earn industry-recognized certifications before graduation.

“The whole idea is, if you have an idea, you can come in and try to make it real,” Preston explained. Luke

Robotics competitions like this one take those skills out of the classroom and put them into motion.

Students code autonomous routines. They design mechanisms to grip, stack, or score. They analyze how robots interact—not just with game elements, but with each other.

And in Unified competition, they learn something else: how to communicate, adapt, and collaborate with teammates who bring different strengths to the table.

“It’s always fun to include everybody,” Preston said. “You learn from each other.”

Students Telling the Story—Live

(Caleb Gosdin leads commentary on live stream.)

(Caleb Gosdin leads commentary on live stream.)

Encompassing the competition floor, another team of students was working just as hard.

Wylie High School’s Audio/Visual class livestreamed the entire event through Bulldog Productions on YouTube. Fifteen students rotated through camera operation, switching, graphics, and audio—capturing every match in real time.

On the microphones were ninth-grader Caleb Gosdin and senior Trenton Forrester, providing live commentary for hours.

“This isn’t a normal sports game,” one student joked early on—but the challenge was real. Keeping energy high, explaining rules on the fly, and filling airtime between matches takes practice. And by midday, Gosdin and Forrester were doing it while juggling class responsibilities.

They didn’t miss a beat.

The result was authentic, student-driven coverage—exactly the kind of real-world experience Wylie ISD aims to provide.

A Model That’s Built to Last

According to Hortenstine, the strength of Unified robotics lies in its structure.

“The rules already worked,” she explained. “We didn’t have to modify or lower expectations. We just set the bar—and the students met it.”

That philosophy aligns closely with the mission of the REC Foundation and VEX Robotics, which focus on access, rigor, and opportunity.

At Wylie ISD, that alignment is intentional.

Junior high students competing on VEX IQ fields today can graduate into VEX V5 in high school. Skills build. Confidence builds. Relationships build.

“This is how programs grow,” Hortenstine said. “And how students grow with them.”

More Than a Tournament

By early afternoon, batteries were drained, robots were packed away, and the PAC slowly returned to its usual shape.

But the impact of the day lingered.

Students who might not have crossed paths before were laughing together. High school mentors had modeled leadership without being asked. Junior high students had competed at a level many never thought possible. And adults watching from the sidelines saw something that went far beyond STEM education.

“Today wasn’t really about robotics,” Preston reflected. “It was about community.”

That sentiment captures the heart of what’s happening at Wylie ISD.

Robots are the tool. Learning is the pathway. But the real outcome is connection.

And on a Tuesday in January—made possible by a group of students and a teacher who gave up a holiday to make it happen—Wylie showed exactly what it looks like when education is designed to bring people together.

It’s more than robotics.

It’s great to be a Wylie Bulldog.

View More Below: